|

| Georgia farmers haul fertilizer to their barn — by horse wagon, you will note — in 1940 |

|

| This creaky old barn is of no use to anything but mice and clinging vines |

These are common scenes down country roads across America.

|

| This Pennsylvania Amish Country corn crib is practically bursting with cobs |

And how many square dances filled the barnyard with music there? There’s a reason why the classic country-music show called the “Grand Ole Opry” is staged in a Nashville, Tennessee, auditorium that is decorated like a barn.

|

| If a skyscraper is a symbol of the city, a barn is a telltale sign that you’re in the country |

The farmer and his neighbors would gather on a piece of high ground to raise a sturdy, all-in-one structure to shelter his livestock, store his grain, and protect his wagon. Alongside many a barn, too, rose simple corn cribs or much taller silos. The latter stored silage — fermented green fodder such as chopped hay, alfalfa, clover, or shredded corn — that compacted tightly, keeping out air and pests and preventing spoilage. Silage seems rank to humans, but cud-chewing animals like cattle and sheep find it tasty.

|

| Another Amish Country scene. Here in central Pennsylvania, and in Wisconsin in the Midwest, too, most farms are tidy and prosperous |

|

| The barn may belong to this girl and her family, but we can see who has the run of the place |

I should pause here to make it clear that, as a child of suburbia, I have visited and very much appreciate the strength and symbolism of barns and the men and women who built and maintain them. But most of what I know about these iconic structures came from my mother and uncle, raised in “the country” in Pennsylvania’s Allegheny Mountains, from childhood stories like Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House on the Prairie, from numerous farm visits — ever watching where I stepped — and from a number of neat Web sites.

|

| Neighbors arrive for an auction at, or perhaps of, a Vermont farm in 1940 |

Where were we?

Ah, yes. As the number of family farms dwindles before the onslaught of consolidation and suburban sprawl, many barns that survive have become nostalgic landmarks, even to those who have never set foot in one.

|

| This is a bank barn in Illinois. You can see that the farmer built a long, earthen ramp up to the second level to facilitate the unloading of grain |

|

| You can see the long forebay on this barn along the old Lincoln Highway, or U.S. Route 30, in Pennsylvania, where the owner is obviously a historian and artist, or art lover |

George Washington, the nation’s first president and a prominent Virginia farmer, discovered the advantages of a round barn or round-appearing structure with 12 or 16 sides. They’re a favorite of mine, and I’ll have more to say about them anon.

Massive and relatively unadorned barns had the simplest of decorations. Chief among them was their color — usually red because reddish ferric oxide was the cheapest pigment and acted as a modest preservative. But in poor regions such as southern Appalachia, where farms were less prosperous, many a barn went unpainted until an

By the way, if you’re tempted to grab a brush, you should know that it can take a single person three summers and 200 liters [53 gallons] of paint to cover a good-sized barn. Check back with me on Twitter in a month or two and let me know how it’s going.

|

| Here’s a creative bit of barn art for sure, in Wisconsin. Note that the Mona Lisa is a big Green Bay Packers football fan |

Of course, barn aficionados like me would argue that barns themselves are works of art.

Of literature, too, though the best-known “barn quote” isn’t very grand: “It’s too late to close the door after the horse is out of the barn,” goes an old proverb, or words to that effect. The late, droll television host Johnny Carson — once a Nebraska farmboy — had a cute one: “I was so naive as a kid that I used to sneak behind the barn and do nothing.” Sam Rayburn, the colorful Texan who ran the U.S. House of Representatives as its speaker for 17 years, once wryly observed, “It takes a good carpenter to build a barn, but any jackass can kick one down.”

|

| Can you find anything not to like about this beautiful scene on a rapeseed farm in Idaho? |

|

| You would probably write the same caption I would for this photo of Carol’s: “Seen better days” |

Others in “the country,” including city refugees trying out the rural lifestyle, find they have no real use for a barn and raze it to make room for a garden or more rows of corn.

|

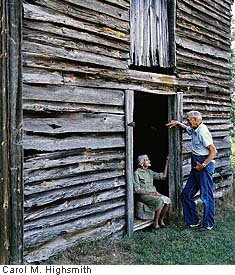

| That’s Carol’s Aunt Kate and a neighbor at the North Carolina barn where Carol helped “sucker” tobacco, meaning she would pull auxiliary shoots called “suckers” from the leaves |

But an incredible array of historical societies, professional and amateur architects, Internet Web sites, collectors’ groups, and just plain barn lovers have rescued old barns. The National Trust for Historic Preservation not only helped save hundreds of barns through its “Barn Again!” program, it even staged an old-fashioned barn-raising inside the National Building Museum in Washington in 1994. Needless to say, that building has a really large atrium.

As for round barns, there’s an old American saying about people who throw a baseball or a rock or a snowball and miss their targets entirely. They throw so poorly, they “couldn’t hit the broad side of a barn.”

Round barns, though, don’t have a broad side.

|

| This is not literally a round barn. It’s a nonagon, a barn with nine sides in Door Prairie, Indiana. But a nine- or 12- or 16-sided barn has pretty much the same effect as a round one |

Carpenters discovered that round barns required less stone or wood than rectangular barns, thus saving on costs. Because their roofs are supported by the one circular wall, no columns are needed. So there’s more room for livestock and hay — and dancing! Midwesterners learned, too, that high winds – even tornadoes – that would pulverize an ordinary barn often glance off a round one.

|

| This is the classic: the Arcadia Round Barn on Route 66 outside Oklahoma City, Oklahoma |

Over the years the round barn was — and still is — the town’s favorite dance spot and one of the most-photographed buildings along scenic, two-lane Route 66 between Chicago and Los Angeles. The Arcadia Round Barn may not be one of the world’s Eight Wonders, but it’s among Oklahoma’s top ten for sure.

In the 1970s, the barn was abandoned. Slowly it began to bulge and slump to the east, until a group of citizens bought it and fixed it up. They pounded telephone poles into the ground all around the barn, wrapped heavy guy wires around them and the barn, and pulled until the old red barn was upright again. That caused the roof to collapse, but they made a new one.

|

| This old Tennessee barn hasn’t exactly been restored. But was put to another use, as a rural garage and repair shop |

All these “adaptive re-uses” preserve barns as photogenic relics, but, as I once wrote in a VOA “Only in America” essay, “Almost always, something is missing from this happy picture: a cornfield or a pasture – or a pig, or a cow!”

It beats the alternative of a forlorn, collapsed shell or no barn at all, however.

|

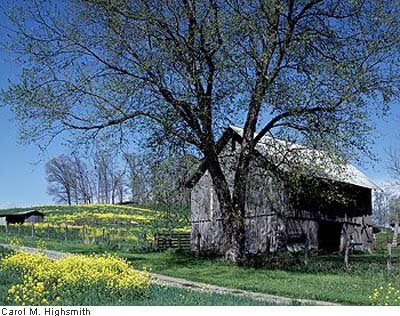

| There’s little in life that’s more peaceful and refreshing than springtime in the country |

|

| A barn owl: the farmer’s friend |

***

Uncle Walter

As you know from encountering my “Wild Words” each week, I like and use a lot of unusual English words. In America, one of them needs no definition beyond the mention of a person’s name.

The word is avuncular.

And the name is Walter Cronkite.

Most of the obituaries of this lion of television anchormen, who died July 17 at age 92, reach for that word in describing him. It has to do with the twinkly qualities of a kindly uncle. Note the “unc” in both words. Genial, unthreatening Uncle Walter — he on the screen and we at home were on a first-name basis, it seemed — invited us onto his knee for story time.

Not happy stories, often, but important ones that we needed to hear.

Today’s media environment glorifies action, sizzle, and showmanship. As Tom Knott points out in the Washington Times, the hottest medium, the Web, has as “its principal objective [to] push out gobs of content, create traffic, and inspire comments.” There and on TV, there’s no one who, by consensus, we all turn to, count on, and trust. You like her. I like him. Sets down the street are tuned to a hundred others whom those people prefer.

|

| A young Uncle Walter |

Uncle Walter had no sizzle at all. For 21 years, until his retirement in 1981, he sat stiffly on camera — as you or I would — as if the limelight discomfited him. But we grew comfortable with him. There were few yuks on Managing Editor Cronkite’s CBS Evening News. A touch of bemusement, a twitch of his little moustache, or an arch of his raging eyebrows was as far as he’d go.

It’s hardly original thinking, but it bears repeating: When Walter Cronkite signed off “That’s the way it is,” that’s the way America was, all right, that night.

I doubt we’ll be using “avuncular” much any more.

TODAY'S WILD WORDS

(These are a few of the words from this posting that you may not know. Each time, I'll tell you a little about them and also place them into a cumulative archive of "Ted's Wild Words" in the right-hand column of the home page. Just click on it there, and if there's another word in today's blog that you'd like me to explain, just ask!)

Gambrel. This is a French word, roughly meaning “meat hook” and is often applied to the style of roofs, especially on barns. It reflects the abrupt change in pitch of the roof.

Haymow. A loft where hay or other grain is piled, ready to feed animals below. “Mow” as used here, by the way, rhymes with “plow,” not “toe.”

Hex signs. In the United States, hex signs are Pennsylvania Dutch folk art meant, despite their name, to bring farmers good luck, not cast a spell on their neighbors. They are intended, however, to ward off evil and others’ hexes and to “protect” the site from bad luck, which is one way of bringing good fortune.

Kudzu. An aggressive vine that can completely cover abandoned structures and strangle trees and other plants. Kudzu was introduced from Japan as a decorative plant at the 1876 U.S. centennial fair in Philadelphia. Little did people know that the invasive species would become a nightmare as it ran rampant, especially in the hot, humid South.

Please leave a comment.

1 comment:

This in my favorite Barn of all time!!

http://www.nps.gov/tapr/photosmultimedia/virtual-tour-limestone-barn-1st-level.htm

Flips in Branson, Mo.

Post a Comment