|

| There’s even an interstate highway sign pointing drivers to an amazing VOA complex |

• a three-in-one museum that chronicles VOA’s story, the saga of wireless communication going back to Marconi, and local broadcasting history in rich detail;

• a large and beautiful park named for the Voice of America where you can hike, fish in a 14-hectare lake, sled down a long hill, get a match going on one of 24 soccer fields or a cricket pitch, bird-watch in meadow that’s an official wildlife preserve, let your mutt loose in the “Wiggly Field” dog park, and even get married!

• a university learning center that also carries the name of the Voice of America;

• and even a good-sized VOA shopping center, of all things.

You would surely assume that such an immersion experience would be in Washington, surrounding VOA headquarters on Independence Avenue and the National Mall. Or somehow squeezed into downtown New York City, where most VOA programming originated during the war.

Those choices are too obvious, of course. I must be teasing you about the location for a reason.

|

| OK, so where is Cox Road? |

To picture their location, take your right hand and make a “V for Victory” sign of the sort for which Britain’s wartime prime minister, Winston Churchill, was famous.

Your fist is the pleasant and prosperous Midwest city of Cincinnati, Ohio. And your two uplifted fingers are busy interstate highways, the index finger heading north toward Dayton, Ohio, and on to Detroit, Michigan; and the middle finger angling northeastward to Ohio’s capital city of Columbus and the Great Lakes port of Cleveland.

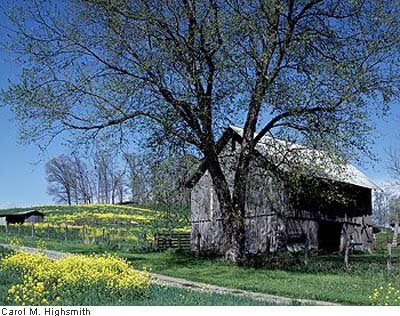

Inside the V, what was once the rural township of West Chester has exploded from 39,700 population in 1990 to more than 62,000 today as housing subdivisions, shopping malls, business parks, hospitals, and freeway exit clusters of gas stations, restaurants, and motels have gobbled up almost every clod of dirt.

|

| We’re getting warmer! |

Why there?

As announcer Fred Foy intoned on the old Lone Ranger radio show in the 1940s, return with me now to those thrilling days of yesteryear for the fascinating answer.

|

| Powel Crosley at age 20 or so, before he made his first million |

|

| Lots of people drove Crosleys home and grabbed a beer or sandwich from their Crosley refrigerators in the 1940 |

Powel Crosley became intrigued with broadcasting when his son asked for a radio set as a “toy.” Revolted by their exorbitant cost, Crosley was soon building radios and their components himself. By 1924, the Crosley Corp. was the world’s largest manufacturer of desk radios and large radio cabinets of the sort you see families gathered around in old photographs.

Crosley the radio man wanted to give people a good reason to buy his product, so he constructed a 20-watt transmitter in his home and began broadcasting to his neighbors.

Within ten years, the entire country would be listening, not through some network but to Crosley’s WLW – “The Nation’s Station” in Cincinnati – which generated its own elaborate programs, including the first “soap opera” using a resident company of actors and musicians. Many of them – singers Doris Day and the Mills Brothers among them – would become American superstars.

Broadcasting on medium wave at 500,000 watts – ten times the power of any other U.S. radio station then and to this day – beginning May 2, 1934 with the throwing of a switch by President Roosevelt in Washington, WLW bounced a signal off the ionosphere from coast to coast and beyond. Rival stations complained bitterly of unfair competition and interference with their signals. And when some of them began haranguing the federal government for equal power to mount their own superstations, Congress in 1939 rid itself of the controversy by capping every station’s power, including WLW’s, at 50,000 watts.

|

| This early informational booklet shows the unusual shape of WLW's 224-meter (735-foot), 200-ton tower that blasted its signal clear across the continent |

Fast forward to the early days of World War II, when Nazi Germany, too, had developed 62 powerful transmitters, shortwave in this case, pointed across Europe and reaching as far away as South America. German broadcasters poured out propaganda aimed at softening resistance to Nazi aggression and diverting America’s attention. Japan, too, operated 42 long-range transmitters flooding the Asian nations it was in the process of subjugating.

There was no equivalent American response, since the nation was trying mightily to stay clear of war. The signals of only 13 shortwave stations, programming innocuous entertainment, emanated from America’s shores at the time.

Powel Crosley’s WLWO – or WLW Overseas – was one of them. From two towers next to the WLW monster in those corn and alfalfa fields, it beamed orchestra music, comedy shows, crime dramas and “westerns” to Europe and Latin America with 75kw of shortwave power. Following Japan’s bombing of the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, in December 1941, and America’s immediate declaration of war on Japan and Germany, President Roosevelt summoned titans of industry and pleaded for help in countering Axis psychological warfare. WLWO began beaming German- and Italian-language broadcasts supplied by the Voice of America’s predecessor agency, the Office of War Information, operating out of New York. WLWO broadcasters like Robert Bauer, who had escaped Nazi Germany by an eyelash, gave the Third Reich a dose of its own bluster. Bauer, an Austrian like Adolf Hitler, could mimic the Führer’s speech impeccably. He would give faux rally speeches in which “Hitler” would dissolve into stark-raving lunacy – which, of course, wasn’t far removed from reality. The real madman, in turn, was heard to rail against “those Cincinnati liars.”

WLWO and other American-based shortwave stations also carried the very first words of the new Voice of America in February 1942, when newsman William Harlan Hale said in German from New York, “The news may be bad or the news may be good; we will tell you the truth.”

During a break in the president’s meeting with the moguls, Crosley Corp. Chairman James Shouse called his top engineer in Cincinnati and asked if the company could build 200kw shortwave transmitters with directional antennas that could be aimed at Europe, Africa, and South America.

“I don’t know, but I will sure give it a hell of a try,” replied the engineer.

|

| These are some of the mammoth pillars, sunk far into the ground, that supported VOA’s Bethany towers |

Needless to say, the Bethany project got “AA-1” priority, obtaining all the glass vacuum tubes, steel, and copper it needed, despite the strict wartime rationing of such materials.

There in bucolic West Chester within a year and a few days, Shouse’s men, including Clyde Haehnle, who is still an active broadcast-engineering consultant and one of the VOA museum’s board members, constructed an impressive building the size of a small city’s airport terminal.

|

| Here’s the Bethany transmitter site and some of the towers that it controlled. |

|

| Three of the old Crosley transmitters, photographed at the VOA Bethany site in 1968 |

“These shortwaves are not like those of our standard broadcast band,” an early VOA broadcast informed its audience. “They are the siege guns of radio, the heavy artillery – guns of war that can hurl explosive facts against weapons of lies and confusion, anywhere in the world.”

|

| A Collins transmitter panel, including its signal’s “flow chart” |

According to one report, the Crosley engineers had to overcome “horrendous” technical problems in mounting the new transmitter site. “New tubes had to be designed [and built from scratch], 24 high-gain rhombic antennas improved, [and] ‘re-entrant termination’ advanced to keep antennas from simply melting. . . . It was the most sophisticated antennae system ever devised.”

|

| Funny things happened out in the antenna field from time to time. Not always so funny if you were involved, however |

The entire complex was surrounded by chain-link fence and closely guarded by military sentries, some of whom slept in the observation tower above the transmitters and control rooms. Guards would remain through the Cold War years, after which engineers could finally allow in curious citizens and passersby for impromptu tours.

You would not have found a single microphone at the Bethany site. It was pragmatism – and paranoia – at work. What if enemy agents were to seize control of transmitters that could be redirected to different parts of the world in ten minutes?

|

| This model of VOA’s Bethany station, sold as part of fundraising for the new National Voice of America Museum of Broadcasting, includes a good look at the observation tower |

In 1945 Powel Crosley, still determined to build and market inexpensive automobiles, sold WLW and all other Crosley broadcasting properties, though Crosley engineers continued to operate VOA’s Bethany site until Voice of America personnel took over in 1963.

|

| Early VOA Bethany Station engineers weren't a jeans-and-T-shirt crowd. The dress and attention to detail were professional all the way |

|

| Down goes one of the Bethany towers. Old-timers had wanted to keep them, but the prevailing view was that even unelectrified, they were a safety hazard, too tempting to daredevil climbers |

|

| With the closing of the Bethany station, it was time to tell its story, if succinctly, in a historical marker |

In 2000, shortly after the Bethany site was formally transferred to West Chester Township, Bill Zerkle, the parks and recreation director, was visited by his boss. “We’re getting the VOA property,” he told Zerkle, and as part of the agreement this old transmitter building is to become a museum. “So buddy, you go for it,” Zerkle recalls the superior’s instruction.

|

The preserved VOA transmitter building and grounds are dwarfed by the rest of the site. They lie at the bottom middle, to the right of the shopping center parcel |

|

| Miami University’s “Voice of America Learning Center” has an impressive home |

|

| In addition to lovely natural features like this fishing lake, the VOA Park will one day add a performance amphitheater, whose crowds may be ripe customers for the VOA museum |

The little piece that remained of the project, including the transmitter building, was left to the township for that unspecified museum.

Zerkle, who left the parks department to become president and CEO of the National Voice of America Museum of Broadcasting in 2007, set up shop in the deserted, unheated building. It had been toasty warm in the days when its transmitters, full of large and red-hot tubes, were, in architect Fearing’s words, “sucking up 3 million watts” of power; so hot were the tubes that some transmitter components had to be cooled in vats called “water jackets,” whose rising steam heated the building. Now Zerkle was spending his winters in sweater, coat, and hat, surrounded by little space heaters. He and volunteers from a group called the Veterans’ Voice of America Fund, later renamed The National Voice of America Museum of Broadcasting Fund, began money-raising, and in 2008 they secured enough funds to create the museum master plan.

The “National Voice of America Museum of Broadcasting” will one day, perhaps soon, incorporate four “visitor experiences,” two of which are already in place:

|

| Just a few of the items, some of them now truly priceless, at the Gray’s Wireless Museum portion of the building |

|

| Some of the displays at the Greater Cincinnati and Ohio Museum of Broadcasting wing of the building, such as this children’s-show exhibit, are lighthearted |

A third component, now under construction, is a reincarnated working amateur, or “ham” radio station, WC8VOA, whose operations will be fully visible to visitors. Technicians had run the amateur station on the premises during the Bethany station’s operating lifetime.

|

| A restored control room console |

The pièce de résistance will be a Grand Concourse and a VOA Gallery. The former will feature an overhead oval screen so that the story of "America's Voice" can be dramatized using a 360-degree multi-media presentation. Actors will also portray VOA notables and broadcasters. The interactive VOA Gallery will use artifacts, hands-on displays, and a large-scale model of the Bethany Station to focus on the station’s role in World War II and the Cold War.

The museum will also offer a gift shop, a grand tour of the restored VOA transmitter facilities and control room from half a century ago, and, outside, such experiences as walks along paths carefully sited along the azimuths of the Bethany antennas’ signals. Maybe even the restrooms will be part of the tour. “There were two,” Gray’s Museum Secretary-Treasurer Bob Sands notes. “One for employees and one for gentlemen”!

|

| Visitors are sure to find the site’s switching matrix fascinating |

The degree to which the federal government’s Broadcasting Board of Governors (BBG), VOA’s parent agency in Washington, will support the VOA Museum in Ohio with funds, artifacts, or special permission to present VOA programming has yet to be determined.

“What these people here did was to pull together the inventions that evolved from Marconi and create state-of-the-art technology that enabled professional VOA media people to tell the truth about this great country. It’s a story they believed in – still believe in – and one that resonates with the people of this area.”

TODAY'S WILD WORDS

(These are a few of the words from this posting that you may not know. Each time, I'll tell you a little about them and also place them into a cumulative archive of "Ted's Wild Words" in the right-hand column of the home page. Just click on it there, and if there's another word in today's blog that you'd like me to explain, just ask!)

Bucolic. Rustic, pastoral, countrified.

Soap opera. A serialized radio, and later television, romantic drama, aimed at a female audience and frequently sponsored by the makers of soap powders.