But there are four other boroughs, or administrative divisions, including one that was once every bit as powerful and prestigious as Manhattan. And except for following the New York Yankees baseball team in the Bronx or the New York Mets in Queens — or reliving the glory days of the Brooklyn Dodgers team that split for Los Angeles in 1958 — most Americans don’t give them much thought.

I’d wager that 7 out of 10 of us couldn’t even name the fifth borough, not mentioned above. Nor could they tell us much about it, even though close to half a million people live there. That puts this mystery borough ahead of entire big cities such as Cleveland, Ohio; Kansas City, Missouri; and Miami, Florida, in population.

One hint: To a visitor it seems as if as many seagulls as people live in this place. More later.

In 1898, when Manhattan Island seemed full to capacity before cities knew how to grow up as well as outward, New York City planners simply annexed their neighbors and created five boroughs, instantly doubling the population and tripling the city’s size.

Not everyone submitted meekly. Brooklyn, a proud, independent city of 850,000 people, had been connected to Manhattan, but only via the world’s longest suspension bridge — its bridge, the Brooklyn Bridge — and residents were starkly divided over the referendum to create a Greater New York. Its business leaders favored the idea on the myopic assumption that Brooklyn, with its bustling shipyards, would dominate the giant new city.

After all, at that point Brooklyn was the nation’s fourth-largest city, behind only Philadelphia, Chicago, and the leaner New York. Even Emma Lazarus’s fabled poem, “The Colossus” — “Give me your tired, your poor/ Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free” — chiseled on a tablet at the Statue of Liberty, speaks of “twin cities,” of which Brooklyn was one.

But to Brooklyn’s dismay, it was Manhattan where money and power would concentrate. Brooklyn receded into a mostly residential, and resentful, satellite of "The City."

Queens's westernmost villages, just past Brooklyn on Long Island, were already Manhattan’s vegetable garden. Foreseeing improved roads and city services, they agreed to annexation.

But the villages in the middle of the island declined the invitation to unite with the big brute of a city. In 1899 they formed their own county, Nassau, and went their own way. Ritzy Suffolk County, even farther east on the island, never had to deal with all this citifying.

North of Manhattan on the mainland, much of the Bronx had already been gobbled up by New York City. When the remainder was asked whether it, too, wanted to join in the fun of building a super city, its residents said no.

But the whole of the Bronx was annexed anyway. Not sure how that got done.

The folks on Staten Island — aha! the mystery fifth borough is revealed — succumbed quietly to annexation.

Let’s take New York City's four add-on boroughs one by one:

Brooklyn is a far different place from congested Manhattan, for sure. But not an inferior one by any means. In a New Yorker magazine essay in July 1996, Kennedy Fraser wrote, “Roses smell sweeter in Brooklyn [and] even the birds sound innocent, like youths from the old neighborhood singing a cappella.” Brooklyn is New York’s most nostalgic borough, reminiscing to this day about “dem Bums.” They were the aforementioned Dodgers — named for the nimble “trolley dodger” baseball fans who wove their way past Flatbush streetcars to the stadium, Ebbets Field.

Flatbush is one of many colorfully titled Brooklyn neighborhoods. Gravesend, Bath Beach, and DUMBO — an acronym for “Down Under the Manhattan Bridge Overpass” — are others. How’d you like to live in DUMBO?

Like the other boroughs, Breuckelen was chartered in 1646 as a place for the Dutch to build country manor homes and vegetable farms. Ferry service to Manhattan was spotty until Robert Fulton demonstrated his new steamboat in 1807. Brooklyn’s own city center grew on high ground, surrounded by stately brownstone row houses and apartment buildings.

Brooklyn was inundated by immigrants, beginning with Irish and Germans in the 1830s. It was poor Irish — already speaking English with a brogue and trying to cope with American idioms mixed with remnants of Dutch — who first developed the much-mocked “Brooklyn accent.” Hollywood characters like the “Bowery Boys” shamelessly exaggerated it: “Youse meet me at Toity-toid and Toid Av’nue.”

So fiercely did Brooklyn trumpet its self-sufficiency, even after it lost its independence, that other New Yorkers grumbled about the bristling “Brooklyn attitude.” For decades, its docks and marine terminals were more than a match for Manhattan’s. The historic U.S. Civil War ironclad warship Monitor had been built and launched there in 1862. And if not a landmark, Floyd Bennett Field, the modest airfield that juts out into Jamaica Bay, should be on any trivia-lover’s tour. It was there in 1938 that Douglas “Wrong Way” Corrigan took off on a westward flight for California and ended up, 28 days later, in Ireland.

Brooklyn has its own spectacular, 213-hectare (526-acre) green space, Prospect Park, designed by the same men who created Manhattan’s treasured Central Park. Revered as the “City of Churches,” Brooklyn offers a full day’s tour of impressive houses of worship.

The Brooklyn Academy of Music is the oldest continuously active performing-arts center in the nation.

The Brooklyn Botanic Garden has an unusual, if not unique, Garden of Fragrance especially for the visually impaired. And an abandoned subway station in Brooklyn was chosen as the city’s transit museum.

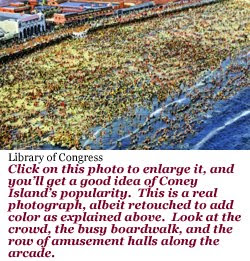

I’ve spent many days in Brooklyn — vicariously — at Coney Island. Along with Atlantic City in New Jersey, Coney Island (actually a peninsula) provided the setting for hundreds of idyllic picture postcards in the early 20th Century, when family fun at the shore was considered exotic.

People wrote “Wish you were here” to their loved ones and friends from the Luna Park amusement rides, Surf Avenue game arcade, and Dreamland Tower and lagoon at Coney Island.

And despite the common tale that the Statue of Liberty was the first sight beheld by New York-bound immigrants to the New World, it was actually a huge elephant. Not a real one or a big model. The Elephant Hotel (and brothel) at Coney Island was built in the shape of a pachyderm.

The Bronx got its unusual name from the area’s first settler, Danish immigrant Jonas Bronck, or more particularly, the Broncks’ family farm. With the building of King’s Bridge over the Harlem River around 1700, the Bronx became New York’s mainland connection. Farm-fresh Bronx produce soon found its way onto Manhattan Island, as did fresh water, piped in from clear springs. Until the 20th Century, the Bronx remained a land of farms, manor homes, and modest factories — including a giant snuff mill.

The Bronx was one of the first parts of New York to succumb to rampant subdivision and apartment construction that would lead to an oversaturation of low-income housing. The sad cycle of decay and abandonment followed, and wealthy landowners sold off their Bronx estates in favor of places in the “real” country, farther from the city in Westchester County.

Years later in the 1970s, when the people who took their place themselves moved farther out, to Westchester or the New Jersey suburbs, whole Bronx neighborhoods were left to the predations of vandals and drug dealers. Even the Bronx’s big courthouse was moved to safer ground, as was the original borough hall. New York University moved out of its Bronx campus entirely.

But the mighty New York Yankees’ baseball team — the “Bronx Bombers” — remained and triumphed. They have played in the “world” championship series 40 times since 1927, winning 27 titles, including last season’s.

Borrowing Jerome Kern’s song lyrics from “New York, New York” that “the Bronx is up and the Battery’s down,” the Bronx is “up” again, and not just geographically. Much of the blight is gone, and new city and private colleges have created a steady employment base. The Grand Concourse, a string of 1930s Art Deco residential buildings, has been renovated. And two New York cultural fixtures — the Bronx Zoo and the New York Botanical Garden — are thriving.

In Queens, the largest and most residential borough with more than 175,000 single-family homes, neighborhood pride has lingered through decades of rapid urbanization. Places like Flushing, Floral Park, and Long Island City have clung to their separate identities.

Flushing, by the way, did not get its name from some Duke of Flushing or a primitive commode. It’s a rough English translation of the Dutch word for “flowing waters,” presumably from a pretty Long Island stream.

One of the most fascinating Queens neighborhoods is Steinway — once a company town built by German immigrant Wilhelm Steinweg, who Americanized his name after his brilliance at building pianos was affirmed. Some of Steinway’s row houses are still in use, and the company continues to craft pianos at a factory in another part of Queens.

Many Queens neighborhoods are 20th-Century creations, their modest homes built to satisfy the demands of returning veterans of world wars I and II. Even after the last farmers departed for Nassau and Suffolk counties, farther out Long Island, the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation retained a 19-hectare (47-acre) vegetable farm. Its barnyard and fields are open to visitors, including amazed inner-city schoolchildren.

Queens’s population explosion was stoked by two worlds’ fairs held in Corona Park in Flushing Meadows in 1939-40 and 1964-65. The first was organized around the Trylon, a huge conical column, and the Perisphere, a giant globe. The star attractions in 1939, though, were the first public demonstrations of television in the fair’s “World of Tomorrow.”

The centerpiece of the ’64 fair was the “Unisphere,” a 43-meter-high structure that represented “Peace Through Understanding.” It still stands, as does a wave-shaped pavilion that today houses the New York Hall of Science, a hands-on science and technology museum.

A truly remarkable remnant of the 1964-65 fair is the Panorama of the City of New York, the world’s largest architectural model, which fills a spacious room at the Queens Museum of Art. It depicts — now ponder this for a moment — 895,000 individual miniature structures at the scale of one inch to one hundred feet (about 2.5 centimeters to 30 meters). Not just familiar bridges and skyscrapers, but also smaller office and apartment buildings and even houses in their exact locations in all five boroughs.

Not really Queens tourist attractions, but receiving plenty of visitors each year, are New York City’s two airports — John F. Kennedy International and the much older La Guardia. I’m not counting the mammoth, newer Newark International Airport over in “Jersey.” LaGuardia dates to 1939. “JFK,” which opened gradually to minimal air traffic in the 1940s, is noted for its futuristic terminals, including the Trans World Airlines hub, designed by Eero Saarinen, the Finnish-American who also designed the towering Gateway Arch in St. Louis, Missouri; and “Black Rock,” the headquarters building of CBS TV and radio in downtown Manhattan.

Nowhere in New York City has the impact of a new tunnel, bridge, or expressway been as dramatic as in Staten Island. Through most of its history, hilly Staten Island, a mere 22 kilometers long and 13 kilometers wide, had been almost an afterthought. It was 37 years after the Dutch settled New Netherland — before they got a foothold on Staaten Eylandt in 1661 following repeated bloody battles with indigenous Lenape Indians.

The English who soon supplanted them called the place “Richmond” after a duke of the time. The name was changed back to Staten Island in 1976 because, or so the story goes, Borough President Bob Connon got tired of hearing the other borough presidents ask him, “How are things down South” — a not-especially-clever reference to Richmond, Virginia.

Well into the 20th Century, Staten Island residents were islanders in temperament as well as fact, savoring their serenity at night and on weekends after ferry rides to and from work in Manhattn. They may have been tied to New York City officially and financially, but the only bridge led to New Jersey. There was plenty of open space around Staten Island’s 62 separate villages and seashore communities. Life was pleasant, safe, relatively undisturbed.

Then, in 1964, the city completed the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge, named for an Italian explorer who first sailed into New York Bay in 1524. The bridge connected the island to Brooklyn on Long Island, changing Staten Island forever. In the classic pattern of moving out and up, tens of thousands of Brooklynites (and others) moved in, seeking a piece of tranquilty. Over the next 20 years, the island’s population doubled, and resort-like Staten Island was soon awash in strip shopping malls and fast-food restaurants. Its winding roads were overwhelmed by traffic.

Remember those seagulls that I mentioned way up top? They became a Staten Island institution beginning in 1948, when the city first dumped its household refuse into a landfill in the island’s Fresh Kills wetlands. Its promise, and everyone’s expectation, was that the dumping would be short-term and the garbage pile limited in size. But 50 years later, the scows were still docking, the trucks were still rumbling, and the stench was still rising. The garbage mound grew taller than the Statue of Liberty and could be seen from space with the naked eye.

But the city has begun converting the big dump into a public park and wildlife sanctuary, Freshkills Park — destined to be three times the size of Central Park.

In every New York City borough, change has brought stresses and challenges. South Asian, Vietnamese, African-American, and Russian neighborhoods have sprung up where Greeks, Italians, European and Syrian Jews, and Anglo-Saxons once carved out enclaves. “We’re a social laboratory,” one Bronx resident told American Way magazine. Old-time New Yorkers worry still about immigrants taking away jobs, eating away at the tax base, abusing welfare. But by now they’re pretty much used to strange foods from multiple cultures, and sidewalks that are a babel of confusion.

For all the complaining, the brashness, the cynicism and gruffness, hard-driving, self-absorbed New York eventually accepted them all.

WILD WORDS

(These are a few of the words from this posting that you may not know. Each time, I'll tell you a little about them and also place them into a cumulative archive of "Ted's Wild Words" in the right-hand column of the home page. Just click on it there, and if there's another word in today's blog that you'd like me to explain, just ask!)

(These are a few of the words from this posting that you may not know. Each time, I'll tell you a little about them and also place them into a cumulative archive of "Ted's Wild Words" in the right-hand column of the home page. Just click on it there, and if there's another word in today's blog that you'd like me to explain, just ask!)

Babel. A gathering or scene of noise or confusion. The name comes from the biblical Tower of Babel, which was built with the idea of reaching heaven. God foiled this plan by garbling the builders’ language so that they could not understand each other.

Myopic. Nearsighted, and often shortsighted, too. One who has a myopic view of things focuses only on what’s in front of him and does not consider the bigger picture.

Pachyderm. Not just an elephant, but one of several kinds of large, hoofed animals that include rhinoceroses and hippopotami.

Scow. A flat-bottomed boat or barge used to haul garbage or bulk freight.

Snuff. A kind of smokeless tobacco made from ground tobacco leaves. It is “snuffed,” or snorted, through the nose.

Vicarious. Indirect or second-hand. One can enjoy an exciting sports event vicariously on television or through a friend’s description, for instance, rather than in person.