Saddle up! We leave Texas in our dust on our trip through the vast American West. Time to head north, across the Red River into Oklahoma.

Boomtown

The West is full of ghost towns, once abuzz with miners, merchants, and even fancy concert halls with gas lamps and red-flocked wallpaper, then abandoned to the elements once the oil or ore played out.

But one boomtown still thrives. Bartlesville, Oklahoma, is one of the most prosperous and sophisticated small towns in the land.

All over Oklahoma, scattered across the sagebrush, one used to see thousands of simple oil rigs called pumpjacks. Driven by “bullwheels” hitched to powerful engines by long thick belts, pumpjacks look like giant praying mantis insects. They bob up and down, up and down, day and night, day after day, sucking oil out of vast pools under the ground.

As long as the oil holds out, that is. Today in these parts, the pool has pretty much dried up, and most pumpjacks sit idle and rusting.

But once, one of the world’s largest oil reservoirs — the Mid-Continent Field, reaching up into Kansas and as far south as Mexico — bubbled directly beneath eastern Oklahoma and the rough-and-tumble town of Bartlesville. Though the region used to be official “Indian Territory” -- where the federal government had forcibly resettled whole tribes of native Americans from distant homelands -- Indians had paid scant attention to the stinky, foul-tasting, black goo seeping from rock formations and the dry prairie itself. They used some of it in balms but mostly avoided it.

But whites knew all about its other, lucrative uses — for kerosene, petroleum jelly and, by the turn of the 20th Century, the gasoline that powered a transportation revolution. Ever since Edwin Drake drilled the first well back in Pennsylvania in 1859, prospectors were looking everywhere for oil.

In 1904, a former barber named

Frank Phillips moved to Bartlesville from Iowa. He founded a bank and had the good fortune to strike oil on his land. Phillips became a millionaire overnight, and he and his brother formed their own oil production company. Phillips Petroleum became the giant, international Phillips 66 oil company that merged with Conoco Inc. in 2002 and moved the company headquarters to Houston, Texas. Still, little Bartlesville thrived and produced an array of fine homes and cultural attractions.

The native tribe thereabouts did well, too. Much of the oil was discovered on Indian land, and whites who wanted to tap it had to negotiate leases from the Osage. It wasn’t long before Osage Indians were the richest tribe in the United States. This was long before casino gambling enriched a number of tribes, including the Osage.

South of town, Frank Phillips bought a big ranch that he called

Woolaroc (for its woods, lakes, and rocks). Today it’s a museum, wildlife preserve, and cultural center that tells the story of the Old West. And of the “Mother Road,” the now-romanticized, two-lane U.S. Highway 66 from Chicago to Los Angeles that runs through these parts and from which the oil company got its name.

But Bartlesville is known for more than oil. From the 1920s into the 1960s, the Phillips 66 Company sponsored the most famous semi-professional sports team in American history. The Bartlesville Phillips 66ers basketball team was composed of former college stars who took jobs with the company. They regularly defeated top collegiate teams and other semi-pro teams like the Ambrose Jellymakers, named for a Denver, Colorado, producer of jams and wines. The Phillips 66ers even defeated a U.S. Olympic team that would go on to win a gold medal in London in 1948.

And Bartlesville is home to an odd-looking building designed by America’s most famous architect:

Frank Lloyd Wright. It’s a 19-story skyscraper, largely made of copper. “Price Tower,” Wright’s only tall building, was built in 1953 for a company that made pipe. The quirky Wright delivered a cantilevered design, inspired by the structure of a tree. Inside, one finds few right angles. Special furniture had to be designed to fit into it.

In Frank Lloyd Wright tradition, the building leaked and was drafty. He was an imaginative architect but a lousy engineer. Nonetheless, the folks in Bartlesville call Price Tower, now an arts center, “innovative” and “the tree that escaped the crowded forest.”

You won’t find many city slickers out on the Woolaroc Ranch, though. Indian exhibits, 30 varieties of native and exotic animals, and a Colt firearms collection are the draw. And a big bullwheel in the oilfield engine house, which the hands fire up for visitors as a noisy testament to the world’s richest oil boomtown.

A Piece of the Prairie

One-third of North America, stretching from what is now Indiana in the Midwest westward to the Rocky Mountains, and northward from Texas deep into Canada, was once uninterrupted prairie, where Plains Indians hunted free-roaming bison, elk, and antelope. Much of that prairie has since been obliterated by cultivated farms, cattle ranches, and bustling cities and towns.

But two stands of the ever-shrinking tallgrass prairie remain in the state of Kansas.

A “sea of grass,” the first Europeans called the never-ending grasslands. Others called it “Great American Desert,” though its rolling, sandy hills were often lush with flowers and grasses. Seeing few trees, the first visitors thought the region unfit for most cultivation. These days, the tallgrass prairie is the rarest and most fragmented ecosystem in North America.

One piece survives in the

Flint Hills of eastern Kansas, whose limestone and shale eroded into grass-covered hills too rugged to farm. Millions of American bison, called buffalo, roamed freely there, and then ranchers brought their cattle to graze.

In 1996, the nation’s only tallgrass preserve was established when the owners of the 4,000-hectare (9,900-acre) Z Bar-Spring Hill ranch sold their spread to a private organization called the National Park Trust — and deliberately not to the state or federal government. If the feds got hold of it, the ranchers grumbled, they’d want more, adding, “We do not want anyone to tell us what we can or can’t do with our own land.”

So the Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve became the nation’s only privately owned national park. Don’t tell the Z Bar boys, but it’s managed by a federal park service ranger!

Tallgrass shoots can reach your waist, depending on rainfall but the individual plants aren’t much to look at. It’s the totality of it all: the wildflowers, arrays of big and little bluestem, switchgrass, or Indiangrass — and the sunrises, sunsets, and summer storm clouds roiling above — that give the place its lonely, majestic character.

Ninety kilometers to the north, on another former cattle ranch, lies a larger remnant of the prairie. This one gets few visitors because it’s operated as a research facility by Kansas State University and the worldwide Nature Conservancy.

This Konza Prairie Biological Station is named for a Kansas Indian tribe. Scientists there study three critical influences on the sweeping prairie: grazing by large ungulates like buffalo and antelope; the effects of the region’s fierce climate (blizzards, droughts, gully-washing thunderstorms); and fire, which the researchers deliberately set from time to time. Controlled burns are useful because nitrogen-rich shoots, tasty to roaming buffalo or cattle, emerge in the aftermath.

I can picture an antelope outrunning, and a meadowlark flying far from, a prairie fire. But a gopher or grasshopper or shrew? I’m told the lucky among these small creatures burrow underground before the flames race overhead. And one species of hawk flies right into the smoke, looking for unfortunate critters that are scurrying for shelter.

Fire, even more than a scarcity of water, is the reason why one sees few trees on the prairie. Grasses and flowers regenerate. Woody plants are toast.

Like parts of the African savannah and South American pampas, the Konza Prairie and Tallgrass National Preserve have never been plowed. And the conservation groups that own them intend to keep it that way.

Middle America, Precisely

Even though a lot of Kansas feels “western” — towns like Dodge City were notorious hangouts for cowpokes and gunslingers and loose women — when you reach Lebanon, Kansas, you’re only halfway to California. Or to Florida; Maine; Washington, D.C.; or Washington State, for that matter.

You are literally in the center of it all: America’s “centroid,” as scientists call it. A milo field right outside tiny Lebanon is the precise center of the U.S. land mass, ignoring separate and far-distant Hawaii and Alaska.

Twenty years ago or so, the milo farmer, Randy Warner, mounted a GPS device onto his truck and drove around his fields, looking for the exact spot where 39 degrees, 15 minutes north latitude crosses 98 degrees, 35 minutes west longitude, as calculated by the U.S. Geological Survey. The USGS told Warner it had put a brass plate there, but he couldn’t find it.

Aside from occasional geography nuts (e.g. Carol and me) who search out such places, there isn’t much excitement in these parts. In 1999, though, Warner helped crews spread 700 bags of marble dust in his milo field as an “X marks the spot” representation of America’s midpoint for “The X Files” science-fiction movie. About 100 folks from Lebanon helped out. That’s a third of everybody in town.

Indeed, Lebanon could be the model for what some call “dying rural America.” It has steadily lost population, lost its grade school, car dealership, and even the community hall where movies were once shown. The town gave up its annual Lebanon Anniversary parade years ago; not enough people were interested in planning or walking in it. So the pace of life is slow. A typical headline in the local paper, the Lebanon Times — circulation 540 — reads, “Dorothy Fisher Has a Wonderful Birthday.”

Talking with Randy Warner, I got to wondering how geographers pinpointed his field as the precise center of the far-flung United States before global tracking satellites soared overhead. They did not, certainly, do what I would have done: stretch a string tightly across a U.S. map from northwest to southeast, and northeast to southwest, then stick a pin where they crossed. That wouldn’t have made sense, since the nation is anything but a rectangle. Not only do our borders wiggle, but the string from Florida would have to cross a lot of water in the Gulf of Mexico.

Later, a retired USGS field chief told me that in their spare time, six veteran topographers laid a map of the United States onto a thick piece of cardboard. Then they carefully cut along the outline. Finally, gingerly, they kept setting and resetting the cardboard cutout on a thick pin of some sort until it balanced.

That very point, tracked down in Farmer Warner’s field, was declared the midpoint of the country. (Sounds to me more like America’s center of gravity, but what do I know?) Amazingly, computer and satellite studies later confirmed that the spot pinpointed in Lebanon was correct!

So I can’t tell you how many angels can balance on the head of a pin, but I know where your cuticle would point if you could lift up the original United States and balance it on your finger.

Oregon or Bust

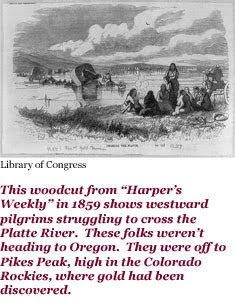

What is by many accounts the greatest peacetime migration in world history took place in the expanding United States in the 1840s and ’50s, when there were only three states west of the wide Mississippi River.

From way across country in the Pacific Northwest, both a government-sponsored surveying expedition and trappers working for John Jacob Astor’s

American Fur Company had sent stories back east of lush, green valleys ripe for farming. When the American economy slid into two straight depressions in 1837 and 1841, thousands of families pulled up stakes and headed west to Oregon in covered wagons, bent on finding them.

This delighted the federal government, which was seeking settlers in the Great Northwest to keep it out of British hands.

An estimated 400,000 people made the trek from Missouri to Oregon. Throughout the West, their wagons wore ruts in the earth that are still visible more than 150 years later. The migrants jammed their wagons with tools and food as well as bedding, plows, rifles, and meager family treasures. Their loads often weighed 700 kilos (1500 pounds) or more.

Little did they know that they would have to discard many goods beside the trail in order to lighten the load through sucking mud and up steep mountain paths. They learned how to hitch their livestock, ford rivers, and spread out and rotate positions in line so that fewer of them had to breathe the choking dust kicked up by the horses and oxen that pulled their “prairie schooners,” the bony milk cows that tagged along behind, and the many family members who walked beside their wagons, all the way to Oregon.

The voyagers started in early Spring, when grass was green and plentiful. They pushed hard, six days a week, knowing that they had to reach the Rocky Mountains before the deadly winter snows. Hostile Plains Indians killed some of the migrants, but many more died from cholera carried in contaminated drinking water.

Nebraska rivers like the Platte, wide and shallow, were quite passable until it rained. Then they would rise and rage and sweep away settlers and animals and wagons. When the sojourners reached

Scotts Bluff in western Nebraska — still a landmark that the Washington Post newspaper once called “an American Gibraltar above the Great Plains” — excitement abounded, for the travelers knew that the great mountains and a big trading post for restocking their wagons lay just a week ahead in Wyoming.

Nebraska has erected signs marked “Oregon Trail Auto Route,” and many landmarks of the old trail can still be seen. They include Windlass Hill, so steep that settlers had to lock their wagon wheels and almost slide down to next valley.

It is one of many places in Nebraska where neither pavement nor plow has buried the Oregon Trail.

Soddies

Have you heard the story of the Three Little Pigs? The one in which a big, bad wolf tries to huff and puff and blow down the pigs’ houses? The first two, made of straw and sticks, were child’s play. But the third was made of brick. No matter how hard he blew, the wolf could not topple it. So the story ends happily — for the third little pig.

There have long been lots of such sturdy brick houses back east. But recreating one was nearly impossible on the wild Great Plains, which had rich soil but little clay to make bricks. As in the wolf story, tornadoes and howling winter winds made short work of anything built of sticks or straw. Lumber was out of the question; there weren’t enough trees.

So the prairie newcomers built homes out of the land itself. Ordinary, everyday prairie sod. Or what the locals cheekily referred to as “Nebraska marble.”

These cheap, safe, and warm houses became “soddies” — strong as a brick home and equally fireproof. Here are the specs:

Sod, first of all, is not dirt. Or not all dirt. It’s mostly tufts of coarse grass, clumped into the soil and held together by the grasses’ tight, twisted network of roots.

A homesteader like William Dowse, the man who built a Nebraska sod house that I visited, took his “breaking plow” and sliced long strips of grass and earth into rows about 35 centimeters wide. Then he took a sharp spade and sliced these long rows of grass and earth into slabs a little less than a meter long.

Though they were nothing but earth and grass, these were called “bricks,” so in that sense, pioneer houses were made of bricks! Grass ones, weighing about 45 kilos (99 pounds) apiece.

Settlers stacked the sod bricks atop each other, grass side down — first rows straight, second rows crossways and so on up — to form the walls of the house. Where they wanted a window, they’d put a heavy plank between rows to hold the sod above.

Somehow, somewhere, the builder would find enough trees to cut wood for windows, doors, and a frame for the roof. The last was the tricky and dusty part. The homeowner would lay the last strips of sod across the roof frame. As a result, one of prairie housewives’ biggest complaints was that little clumps of soil would keep falling from the ceiling onto their nicely swept dirt floors. And into the soup! To catch them, the settlers would tack muslin material beneath the joists.

Talk about sturdy. When a tornado ripped across the Dowse property in 1941, it blew a barn, a windmill, a chicken house, and some sheds to bits. But the soddie was unscathed.

Over time, families up and left most these soddies and moved on. By the time others arrived, society had advanced enough that they could write away to the Sears or J.C. Penney company and have a whole new,

wooden house shipped, in pieces, to them on the prairie.

Never again would dirt clumps in the soup be a worry.

Last Nebraska Stops

Nebraska contains both Midwest-style cornfields and the dry, dusty canyons of the Old West. And you know you’re in the West when you get to the town of Ogallala and see the sign for Boot Hill.

Back in the 1870s, Ogallala was a boomtown like Bartlesville, but not because of oil. It was a cow town, a raucous marketplace for steers on the long cattle trail up from Texas. From there, the Union Pacific railroad shipped the steers off for slaughter in Kansas City. “Shooting up the town was quite a common sport,” wrote Ogallala pioneer settler Harry Lute, of the alcohol-fueled violence that often ensued among the heavily-armed cowboys, in town after their long cattle drives.

Boot Hill was the crude burial ground of 100 or so people — a remarkable number for a town with a permanent population only slightly higher. Some died of snakebites or typhoid or in childbirth, but most were the unfortunate recipients of western justice at the end of a gun or a rope. Horse thieves, card cheats, and gunslingers too slow on the draw were buried with their boots on. Thus the name.

“No church spire pointed upward here,” wrote cowboy Andy Adams in 1875.

Which is precisely why author Larry McMurtry went to Ogallala to research what became Lonesome Dove, his best-selling novel about the legendary cattle drives. And why a TV network produced a highly rated mini-series about the drive, the drovers, Ogallala, and Boot Hill.

“Nebraska’s Cowboy Capital” has grown into a tame town of 4,400 people, not counting tourists, passing hunters, and visiting boaters. Once a year, thousands of cattle, worth millions of dollars, are still sold at Ogallala’s livestock auction.

But Boot Hill has not grown in more than a century.

Something else in Nebraska that hasn’t grown, either, surprisingly, is an amazing procession of sand hills, up near the South Dakota border, 2,000 kilometers from the nearest ocean. There are more than a hundred of these hills, some 125 meters high and (get this!) 30 kilometers long.

These are far different from beach dunes or the great sand seas of Saudi Arabia or China. Many are covered with hardy grasses and flowers. If spring and summer are particularly rainy, you’d swear you were in the lush, green hills of Ireland.

But it’s a fragile beauty. The soil is so loose that cattle wearing a trail, or off-road vehicles vrrooming, along them can tear open the earth’s skin and cause a “blowout” in which sand re-emerges and overwhelms the vegetation. To keep their porous land from eroding or washing away in a flash flood — and fences and telephone poles from falling over — Nebraska Sand Hills residents have adopted the curious custom of tying old tires together. You see strings of them everywhere, and they’re not exactly a scenic wonder.

The sand was formed less than 10,000 years ago during a period of warming and drying, when wind gathered up grains of rock that had broken off the Rocky Mountains and carried them 640 kilometers (400 miles) east across great flatlands before depositing them in huge piles. Because this sand is too heavy to be carried more than a short distance by the wind, the grains actually bounce along the landscape. Since hardy plants (or tires) hold most of the sand in place these days, you don’t run into many sandstorms. But geologists say it’s only a matter of time before another warming period (sound familiar?) kills off vegetation and loosens the Sand Hills to drift far and wide.

Make no mistake: this is barren country. To this day, even counting all the people from little towns, fewer than 1,000 people live in some of the counties that touch this inland sea of sand.

As one Sand Hiller, as they’re called, told me, “When you’re here, you’re nowhere.”

WILD WORDS:

Flocked Flock is a small tuft of fiber, and flocked wallpaper containing flock is not flat as a result. It is decorated with colorful patterns of flocking that one can feel.

Homesteader An American pioneer who had been granted a parcel of land in return for settling the vast expanses of the American West.

Prairie Schooners Heavy pioneer wagons with arching wooden bows that supported billowing canvas covers that gave the wagons a vague shiplike appearance.

Raucous Loud and disorderly, and often a bit lewd, as in some of the hootin’ and hollerin’ inside a western saloon when dusty cowhands reached town after a long cattle drive.

Specs Specifications, as in the blueprints and other particular requirements for an engineering job.