|

| The easiest, though not cheapest, way into town is across the Wabash River on a toll bridge from Illinois. The toll is only a buck, however! |

As a group of screenwriters who go there each year to write told the locals, they can feel their blood pressure dropping the minute they drive into town. Residents and some visitors, including seminary priests from Austria who journeyed to New Harmony last

|

| That’s New Harmony in the distance, though the beautiful trees obscure much of it |

It isn’t heaven on earth, of course. New Harmony has its squabbles, especially between those who wish to preserve its remarkable historic character and those who grump that when they buy a house or a store or a lot, they should be able to do what they damn well please with it. But if clean air, verdant surroundings, a measured pace of life, and culturally and intellectually enriching colloquy are parts of your definition of heaven on earth, New Harmony comes pretty close.

|

| The 1819-22 David Lenz House is a typical example of Harmonist architecture. The walls inside its frame exterior are insulated with kiln-dried bricks |

So the settlers created their utopia on the Wabash. The first of three quite different utopias, as it turned out, if you count New Harmony today as one of them.

The founders called themselves “Harmonists” and their town Harmonie. There were native Indians in the area – hence the name “Indiana” – but most had moved north and west, away from the onrushing white settlers in what was then the Northwest Territory, 10 years before Indiana became a state.

The Harmonists were German “pietists” – Lutheran separatists who sought to create a simple, strict, hardworking community free from the ceremonial flourishes and what they considered the mystical mumbo-jumbo of their faith. Logical pragmatists, they did not buy the notion, for instance, that an unknowing baby could receive faith and salvation with a few sprinkles from a baptismal font. Baptism should come later in life, they believed, as one’s conscious choice, an acceptance of Christ and the Holy Spirit.

|

| Johann Georg Rapp told a town official in Malbronn, Germany, “I am a prophet, and I am called to be one.” The official promptly had him arrested |

The Harmonists were standoffish German speakers who inspired envy among their less industrious English-speaking neighbors. And after 10 years in Pennsylvania, and Rapp’s vision of an even better life on the frontier, Rapp sold Harmonie, “lock, stock, and barrel,” as the saying goes, to local Mennonites – also Germanic but better assimilated into the overall culture – for 10 times what he had paid for the land.

And off they went, down the Ohio River and up the Wabash.

Rapp may well have chosen the location for another reason besides the fertility of its fields. Three years earlier, the area had been riven by a powerful earthquake, centered in New Madrid, Missouri, not terribly far away. (Indeed, one sees sensors, placed by seismologists, at various spots throughout still-tremor-prone New Harmony today). Some say Rapp considered the New Madrid cataclysm another sign from God that the end was near, and his followers might as well get as close to the action as possible.

|

| Harmonie’s earliest cabins were called “blockhouses” because they were made of square timbers. The originals do not survive. These similar examples were imported from a nearby farm |

Then, no doubt to the surprise of their Indiana farmer neighbors, they up and moved again – back to Pennsylvania, founding yet a third town called Economy.

|

| Although some things had changed between Harmonie’s founding and the taking of this photograph in 1892, it gives you a flavor of the old days |

Once again, the Harmonists preferred to sell every stick and stone in New Harmony for a tidy profit and go away.

And in their place came an entirely different sort of utopians: secularists rather than a religious bunch, driven to create human happiness in a communal cooperative based on high-minded ideas and ideals rather than the search for a closer walk with God.

Up the Wabash, to the neat and tidy town that Rapp and his followers had built for them, came what today’s townspeople call a “boatload of knowledge.” It was a barge, actually, carrying Robert Owen and a collection of his very smart friends: scientists, philosophers, educators bent on creating the nexus of a new moral world built upon equal education and social status.

|

| Robert Owen was a brilliant and daring social reformer who brought his ideas, and many idealistic followers, to the Indiana prairie |

The Chautauqua movement was a series of assemblies that met each summer for more than 50 years, spanning the turn of the 20th century. Named for the town in New York State where they were first held, away from the smoke and bustle and cares of the big city, Chautauquans sought to impart intellectual enlightenment, oratorical inspiration, artistic and musical enjoyment, spiritual enrichment, and physical rejuvenation. It was an idea that Robert Owen had tried in New Lanark, Scotland, almost a century earlier.

Owen believed that his ideas would flower even more profoundly in adventurous America, where radical ideas found nourishment. Owen met some Rappites, visited New Harmony, bought the place from Johann Rapp and his followers for $135,000, and invited other eminent thinkers to move there. Many, beginning with those aboard the “boatload of knowledge,” accepted.

|

| Gardens were not hobbyists’ playgrounds in busy Harmonie. Their bounty was an important part of the economy |

But a problem developed almost at once. Unlike Rapp’s Harmonists, Owen’s brainy band had no unifying religious bond; they were individualists with headstrong ideas on how things should run. Rifts developed. So deep, in fact, that roughly half the town, south of Church Street, was occupied by Owen’s family and his disciples; and the neighborhood north of this main street by William Maclure and his followers.

Maclure was a Scottish-born philanthropist and naturalist from Philadelphia – a man so renowned that he was known as “the Father of Geology.” Maclure opened the “Working Men’s Institute,” in a building that still stands, in which common laborers were invited to borrow books and attend lectures aimed at elevating their lot in life. The institute is now the town library.

Robert Owen headed off in search of more intellectual settlers, leaving New Harmony’s management to one of his sons, 23-year-old William Dale Owen. In a piece of local fascination, it is noted that all four of Owen’s sons – Robert, William, David, and Richard – shared the middle name “Dale,” after their mother’s maiden name. Son Robert became a diplomat and U.S. congressman who introduced the legislation that established the Smithsonian Institution in Washington. William ran the local newspaper in addition to the town. David, a geologist for whom the granary was a laboratory, became the state, and then the nation’s official geologist. And Richard, also a geologist, became the first president of Purdue University, up the road in Indiana.

New Harmony was awash in accomplished thinkers, all right, but there weren’t many doers willing to break a sweat tilling the land or producing food and crafts. According to the Web site of the Robert Owen (the elder) Museum in Wales, “Settlers flocked to New Harmony, but most were unsuited to community life, and very few had the necessary skills to farm the land or run small industries. As the settlement became overcrowded the chaos developed. William had to write to his father urging him to send no more settlers.”

|

| Geologist David Dale Owen used New Harmony’s first level for shops and workrooms and the second and third floors for his laboratory and lecture hall |

Thus the town never fell to rack and ruin. Twice it flowered anew, first during a late-19th-century agricultural bonanza in which many Victorian-style downtown banks and mercantile stores appeared; and then during an oil boom in the 1930s and 1940s that attracted fresh out-of-state capital and talent. In that wave, in 1942, came Kenneth

|

| Downtown New Harmony in 1942 looked a lot like any American small town, though perhaps a tad tidier |

And another entity helped return New Harmony to what some would say is a third utopian epoch. It is the Historic New Harmony Society, originally a private, nonprofit preservationist operation that is now a part of the University of Southern Indiana, based in nearby Evansville. Historic New Harmony has helped restore, or keep

|

| This Harmonist labyrinth, re-created in 1939, is planted in accordance with a Harmony Society plan in concentric circles of privet hedge leading to a stone temple |

There’s also another labyrinth in town. This one, flat on the ground, is made of rose granite, not twigs and leaves. It’s identical to one at Chartres Cathedral in France.

|

| Drawing from the Harmonists’ trademark, the golden rose, architect Philip Johnson created a dome in the shape of an inverted rosebud inside his Roofless Church |

|

| The New Harmony atheneum contains several levels of historic galleries containing artifacts and town models |

New Harmony has a few of the accouterments of any small town, including a kindergarten-through-12th grade school, a movie theater to go with the opera house, and a bandstand in Maclure Park. The town’s abundant supply of local musicians makes sure there are plenty of accessible performances there or under the granary’s 205 tons of oaken beams. One in each location takes place on American Independence Day, July 4th, following the annual parade of “floats.” I put the word in quotes because the vehicles are decorated golf carts! – about 50 of them. These carts are the preferred mode of transportation in town, even though there’s no golf course on which to ride them.

|

| It wasn’t New Orleans’ Mardi Gras or New York City’s Thanksgiving Day parade, but New Harmony’s July 4th golf-cart procession was a hoot |

“I live in paradise,” Linda Warum told me. “On Granary Street.”

|

| Stephen de Staebler’s sculpture, “Pieta,” in a courtyard off the Roofless Church, epitomizes New Harmony’s modernist touches in a historic setting |

Of course, that keeps the noise level down and contributes to New Harmony’s air of contemplation.

|

| Former President Taft arrives in New Harmony for the town’s centennial |

The year 2014, just five years away, will mark the bicentennial of this remarkable utopian experiment in the wilderness. By then, the Historic New Harmony Society should have plenty of ideas to work with, including those taken from a wall in the atheneum on which, beginning just this month, visitors have been encouraged to leave their thoughts about what makes a place “utopia.”

|

| New Harmony is a sort of Tranquility Base – not on the moon, but here on earth |

***

More About Utopia

More About Utopia

|

| This is Utopia? I don’t think so! |

Utopian wistfulness reappeared in the 1960s, when communes returned to fashion and eastern mystics and songwriters wrote of the triumph of peace and love over cynical political power. Some say that the vegetarian and “green” environmental movements of today have utopian elements as well.

But before we drift too far off into idyllic reverie, we must remember the words of Clayton Cramer, the California author, historian, and software engineer: “Abandon all hopes of utopia,” he wrote. “There are people involved.”

***

Three Other U.S. Utopian Experiments

Three Other U.S. Utopian Experiments

|

| This is a ca. 1900 shot of the busy Amana Colonies |

Clockmaking and the production of wool and calico augmented the agriculture, and income was shared communally. According to the colony’s Web site, “Amana churches, located in the center of each village, built of brick or stone, have no stained glass windows, no steeple or spire, and reflect the ethos of simplicity and humility. Inspirationists attended worship services 11 times a week; their quiet worship punctuating the days.” More than 50 kitchens, plus a dairy, smokehouse, ice house, gardens, and orchards kept the colonists amply nourished.

The Amana Colonies lasted a long time by utopian society standards. It was only in 1932, during the Great Depression, that the colonists abandoned communal living in favor of the private enterprise that rewards individual achievement, as practiced in the country at large. But the Amana Church survives to this day in the little Amana villages. So do the village store, blacksmith shop, an original 1858 barn, and those tables piled high with hearty food.

|

| This is an early advertisement of the Oneida Community’s Flower de Luce artist-designed silverplate from Good Housekeeping magazine |

The Oneida Community was governed by various committees and by the righteous hand of Noyes himself. At its peak in 1878, it counted about 300 members. By this time, John Noyes had moved to an offshoot commune in Brooklyn, leaving the Oneida leadership in the hands of his son, Theodore. But the younger Noyes was anything but a true believer. He was an agnostic, and a poor administrator to boot. Even though John Noyes hurried back from Brooklyn, the community tore asunder, with many members marrying and leaving the fold. John Noyes fled town after the sheriff knocked with an arrest warrant charging statutory rape. Remnants of the community hung on, making what became world-renowned silver cutlery. The last original Oneida Community member died in 1950, and manufacturing of Oneida silverware ceased in 2004, ending a 124-year tradition.

|

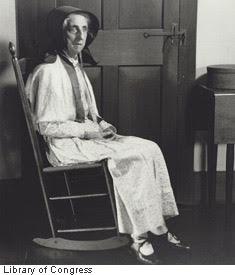

| This Shaker woman was photographed at the Hancock, Massachusetts, Shaker Village in 1935 |

|

| Less than a handful of Shakers remain in the world, at least as of 2006, at this site in Maine |

Thus it was a thin place, too, in quite a different sense.

TODAY'S WILD WORDS

(These are a few of the words from this posting that you may not know. Each time, I'll tell you a little about them and also place them into a cumulative archive of "Ted's Wild Words" in the right-hand column of the home page. Just click on it there, and if there's another word in today's blog that you'd like me to explain, just ask!)

Accouterments. From the French, as you might have guessed, this word describes the trappings or accessories that go with uniforms or dress.

Colloquy. A conversation, especially a learned or formal one.

Gabbing. Chatting, sometimes incessantly. People who talk a lot – and have something worthwhile to say – are said to have the “gift of gab.”

Rack and Ruin. A state of total decay or destruction.

Spunky. Lively, spirited, plucky. The word is said to have devolved from an English and Scottish term for “spark.”

Wistful. Yearning, wishful, usually in a dreamy sort of way.

No comments:

Post a Comment